The French troublemakers’ fourth album is a genre-bending statement. Frontman Aleksejs Macions explains why they’re doing this. When a band calls themselves ShitNoise, it’s either genius trolling or a revolutionary statement. For these French experimentalists, it’s both.

Charades is their fourth record, and it shape-shifts through genres track by track. Noise rock, grunge, hardcore punk, stuff you can’t even classify. Each song wears a different mask. That’s the whole point—it mirrors the album’s core theme: how we lose ourselves constantly playing roles for society. The Armed, Rammstein, IDLES, Viagra Boys—all these influences melted into something aggressive and deliberately uncomfortable.

Aleksejs Macions sat down with us to break down where the provocative band name came from, why they refused to make the album cohesive, what it’s like experiencing an identity crisis while recording an album about identity, and why provoking listeners matters. The release party hits La Zonmé in Nice on November 29—where all this controlled chaos gets road-tested live.

Hey Aleksejs! You know, when I first came across the name ShitNoise, my initial reaction was — okay, this is either a genius deconstruction of pretentiousness in underground music, or top-tier trolling. But then I listened to your material and realized it works on a completely different level. It’s simultaneously a self-aware commentary on the entire noise rock genre and a kind of protective mechanism — like, we named ourselves first, so critics have nothing to work with. Plus, in the context of what you’re doing on “Charades” — this genre chaos, this constant switching between styles — the name sounds almost like a manifesto. So here’s my question: when you chose this name, how intentional was this meta-commentary on the very nature of experimental music, or did it just sound cool and you decided — fuck it, let’s go?

It started as a joke! Our debut single “Hazardous Bitch” was called “Bruitages de merde” (Shit Noise or Shit Sound Effects in French) when it was still in development, it was later translated into “Shit Noise”. We didn’t have a name at the time, and we just told ourselves “Ok, what if we just call ourselves that? Why not, eh?” We also wanted to comment on the whole stereotype of noise and rock music. You know, the generic “rock music is just noise!” comment.

I analyzed “Charades” literally track by track, and one thing struck me — you created an album where each song is a separate genre mask, right? And this directly correlates with the central theme about how we’re forced to wear different masks in society. It’s a brilliant conceptual move because the form literally reflects the content. But here’s what really interests me: when you were writing these tracks in different styles — from charade to charade, if you will — didn’t you feel like you were losing your own identity as a band? Did working on the album itself become a kind of meta-experience of the very concept you’re singing about?

The more we shifted between genres, the more we started questioning who we were underneath. What genre is ShitNoise? Every time we wrote a new song it felt like a different genre, like trying on a new t-shirt or something: sometimes it fit, sometimes it didn’t. There were nights when I thought, do we even have a core sound, or are we just pretending all the time? But then that became the point. Being in this identity crisis while writing an album about identity felt… fitting, I guess.

Okay, let’s talk about the elephant in the room — or rather, the whole zoo of influences you listed. The Armed, in particular, is an interesting choice because they’re known for their anonymity and constantly questioning what it means to be a band in the modern era. And “Charades” has that same deconstructive energy, especially in the production. Aleksejs, you mixed and mastered the album yourself with Clément. How consciously did you use production techniques as another tool to create this feeling of disorientation and shifting masks?

I was in this endless limbo of “should it sound raw or over-polished? Think Nirvana.” Clément helped me find a way to mix both. Some parts sound like they’re from our debut Moments Before Drowning (2023), others like they’re not even ShitNoise at all. That became the whole atmosphere of the record. I guess The Armed influenced that idea because they went from this hardcore band to this noise pop-rock band (ULTRAPOP/Perfect Saviors era) and then back to punk.

Was there a temptation to make the album more cohesive sound-wise, or did you want it to sound like sonic whiplash from the very beginning?

There was definitely a temptation to smooth things out, but that would have killed the album. Charades was meant to be jarring, eclectic, eccentric. If it ever starts feeling cohesive, that means we’re lying.

You took unfinished tracks from Chasse Aux Hiboux and Burn And Leave The Rest and breathed new life into them on “Charades.” This reminds me of what Swans did when Gira constantly revisited old ideas, or how Trent Reznor drags demos from the ’90s into new NIN projects. But here’s the question: those old songs — were they also about masks and identity originally, or did they take on new meaning when you integrated them into the “Charades” concept?

Originally, they weren’t about masks at all, but when I revisited them later, I realized they could be recycled into something that could fit the sonic idea behind the album. Integrating them into Charades felt fitting.

André Caspar appears on saxophone and Razorchild Lynch with a guitar solo on the album. This is interesting because collaborations can either add a new dimension or just become an out-of-place guest verse for the sake of checking a box. What was the conceptual role of these guest musicians in the context of an album about masks? Do they represent another mask the band puts on, or conversely, are these moments of authenticity where you allow other voices to flow into the narrative?

Damn, that’s a good question. Honestly, that’s just what we envisioned for those two songs. For example, on Tiff James (where André plays sax) we wanted to make something that felt like a Viagra Boys track. And with Hospital for Computers, we had this emo Nintendocore idea going on, and since I’m a pretty mediocre lead guitarist, I decided to bring Razorchild into the mix. Both features just fit naturally into what those songs were trying to be.

Mentioning Rammstein as an influence is a bold choice because they’re often misunderstood — they’re masters of provocation through theatricality and irony. And when I listen to “Charades,” I hear a similar approach to how you play with listener expectations. How important is provocation for you, not for shock value, but as a tool to make people think about what masks they themselves wear?

We’re not interested in provocation just to make people flinch. It’s more about testing where comfort ends. If someone feels uneasy, that’s a sign we might have reached a soft spot. Provocation is just another way of asking our listeners to pay attention.

Were there moments on the album where you thought — okay, this might be too much, this might be misunderstood — but decided to go all the way anyway?

Honestly, that’s been the story since our first albums, not just Charades. We’ve always had moments where someone says, “This might be too much,” and the next thought is, “Yeah, but that’s kind of the point.” I think being misunderstood is part of us now. It’s the risk you take when you stop worrying about taste.

A fourth album is an interesting point in any band’s career. It’s not a debut where everything is forgiven, and not a second album with sophomore slump. By the fourth, you’re already established, and you can either play it safe or take a complete risk. You clearly chose the latter. Radiohead on their fourth album released Kid A and changed everything. Did you feel that “Charades” should be your statement album — like, this is what we’ll be remembered for?

Yeah, for sure. Not in an egotistical way, but in a “we might as well burn the house down” way. If this is the album people remember us for, great. If not, at least it’ll confuse the next band that tries to play it safe.

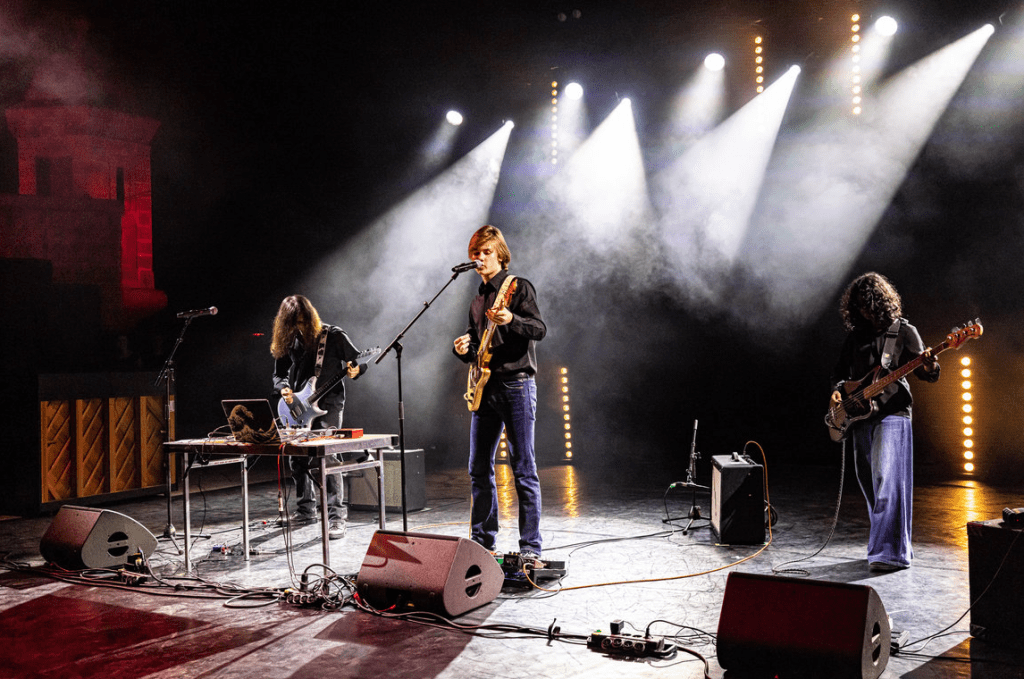

Here’s what particularly interests me in the context of “Charades” — this album sounds incredibly layered and complex in its studio version, with these genre shifts and production tricks. But a live show is a completely different story. Are you currently preparing live shows in support of the album, and if so, where and when will fans be able to see how you translate these genre charades into a live experience?

We’ve already played some Charades songs live before, so we know how different they feel off the record. The point of playing live is its rawness, it’s not meant to sound perfect, it’s meant to feel alive. We’re rebuilding the songs so they breathe on stage, not just repeat what’s on the record. The first big test will be the Charades release party on November 29 at La Zonmé in Nice, France. We’re gonna play a bigger and longer set than what we usually would. After that, we’ll see where it takes us.

*Promoted content. All information provided is prepared in accordance with editorial standards and is intended to offer useful insights for readers.