When Sujae Jung and Wolf Robert Stratmann were studying at The New School in Manhattan, they were hardly thinking about creating an album that would, years later, force a reconsideration of the boundaries of quartet jazz. The Korean pianist and German bassist first played as a duo, then expanded to a quartet, inviting guitarist Steve Cardenas (the very same one who spent years with Paul Motian) and Serbian drummer Marko Djordjevic. Confluence was recorded as a reimagining of five compositions that existed in other formats. The musicians took old material and broke it down to molecules, reassembling it in a configuration where improvisation has consumed composition so thoroughly that distinguishing between them is impossible.

New York jazz is currently in a strange state. On one hand, young musicians on the Brooklyn scene are furiously returning to the spiritual jazz of the seventies, recording long meditative sets with saxophones and African percussion. On the other hand, there’s the academic milieu, graduates of prestigious schools, virtuosos playing the most complex meters and harmonies, but often cold, sterile. Jung Stratmann Quartet falls into the gap between these camps. They’re reflective enough for the academics, but too free for the purists. Compositionally refined enough for conservatory snobs, but too inclined toward an improvisational approach for fans of neat post-bop.

This is both their strength and their difficulty. Confluence is hard to sell to anyone with a direct pitch. This is an album for people who’ve already listened to plenty of jazz, tired of the obvious and searching for music that will work with them, not against them. Five tracks recorded in the studio with minimal intervention—you can hear breathing, the creak of pedals, the acoustics of the room. The result is technically imperfect in places, but absolutely perfect in its aliveness. Far more alive than most contemporary jazz releases, polished beyond recognition.

“Tree Huggers” opens the album with a dialogue between piano and drums, and for the first two minutes I thought this would be yet another European free jazz with pretensions of philosophizing. Jung throws clusters, Djordjevic responds with rolls on the toms, but instead of an explosion, you get dialogue. When the bass and guitar enter, the composition takes shape, Stratmann playing pedal tones here, holding down the bottom while the others wander above. Midway through, Jung takes a solo that develops through repetition of minimal motifs—Philip Glass comes to mind, filtered through a jazz prism. The track ends as it began, refusing to give you any answers.

“Summer Whale” is built on the opposition of bottom and middle—bass and piano. Harmonically, the composition hovers over several centers, like Miles‘s modal jazz, only without his melodic generosity. Cardenas enters late, his notes chosen with indecent precision. Djordjevic here refuses to be a metronome. The middle section is given to a bass solo, and when everyone gathers back together, they play an almost unison line, then scatter. The track is cyclical—ending on the same note it began with.

“This Wine Tastes Very Dry” is the most fragile piece on the album. Jung begins with chords that balance between dissonance and consonance, never definitively choosing a side. Cardenas responds with delay, his phrases mirroring the piano. Djordjevic is almost silent for the first two and a half minutes—brushes rustling so quietly they could be mistaken for air conditioning noise. When he finally makes his presence known, the playing remains crumbly, fragmented. Harmonically, there’s no form here in the conventional sense. European jazz loves these through-composed structures, where everything is written from beginning to end without repetitions.

“The Pull” changes the rules of the game. After three compositions on the edge of atonality, this one returns to traditional jazz. Djordjevic sets up a bossa nova, Stratmann plays walking bass, Jung and Cardenas lead the melody in unison—a rarity on the album. The theme is simple, major, and after the previous tracks, it’s perceived as a revelation. The most accessible track on the album.

“After Sunset” closes the album with a ballad. Jung plays solitary chords with long pauses between them. Stratmann enters arco—with bow, sounding like a cello. Djordjevic works cymbals and brushes throughout the composition, almost inaudible. The middle section is a series of short solos, each musician speaking a few phrases and falling silent. The track concludes with a gradual fade—instruments drop out one by one, leaving the piano with a final chord that resonates, overtones layering, slowly dissolving. The album ends with the same instrument it began with—a cyclical structure.

Comparing Confluence to something specific is difficult because the quartet stands at a crossroads of influences. Echoes of late Motian are audible—the same love of space and silence. There’s the European chamber quality of ECM aesthetics, but without its characteristic coldness.

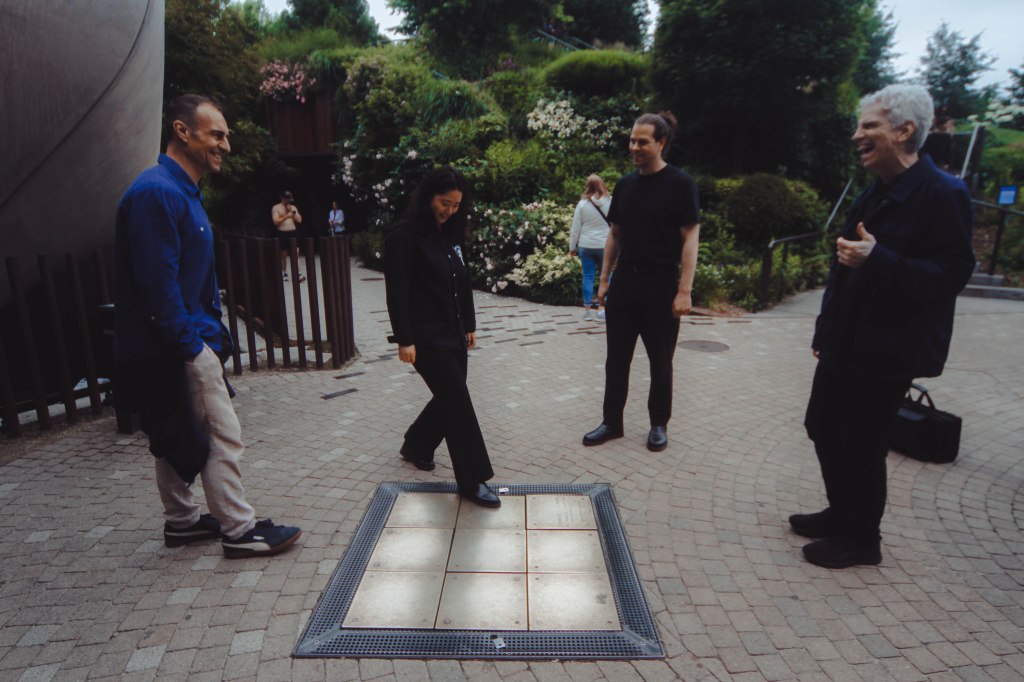

There’s one complaint, and it’s serious—you want more. The longest composition here is just over six minutes. “Tree Huggers” could have been a fifteen-minute exploration, “This Wine Tastes Very Dry” begs for ten minutes minimum. Perhaps this was the producer’s decision—keeping tracks short to maintain attention. Perhaps the musicians themselves decided that conciseness matters more than completeness. In any case, this album is listened to in one breath, simply frozen in place.

The album demands a prepared listener. If your acquaintance with jazz is limited to Kind of Blue and Spotify playlists like “Jazz for Work,” Confluence will seem like a monster under the bed. This is jazz for people who’ve already gone through standards, bop, modal, free, and are now looking for the next step.

It’s interesting how the album will live on. Recordings that demand time and attention rarely become hits, but sometimes they accumulate an audience slowly, through word of mouth and recommendations. Confluence might become an album that people discover a year, two, five years after its release. Jung and Stratmann have built something sustainable over their years working together. Expanding to a quartet with Cardenas and Djordjevic added color and depth without losing intimacy. Four musicians from four countries (Korea, Germany, USA, Serbia) found a common language through jazz, which ceased being an American genre long ago and became an international dialect. Confluence is an album that could only have been recorded in New York, where these cultural streams meet daily on the streets, in the subway, in the clubs.

Confluence is one of the most important jazz releases of 2025, but recognition will come slowly. The album is against trends—against virality, against instant access, against easy consumption. It demands investment of time and attention, promising in return depth and longevity.

*Promoted content. All information provided is prepared in accordance with editorial standards and is intended to offer useful insights for readers.