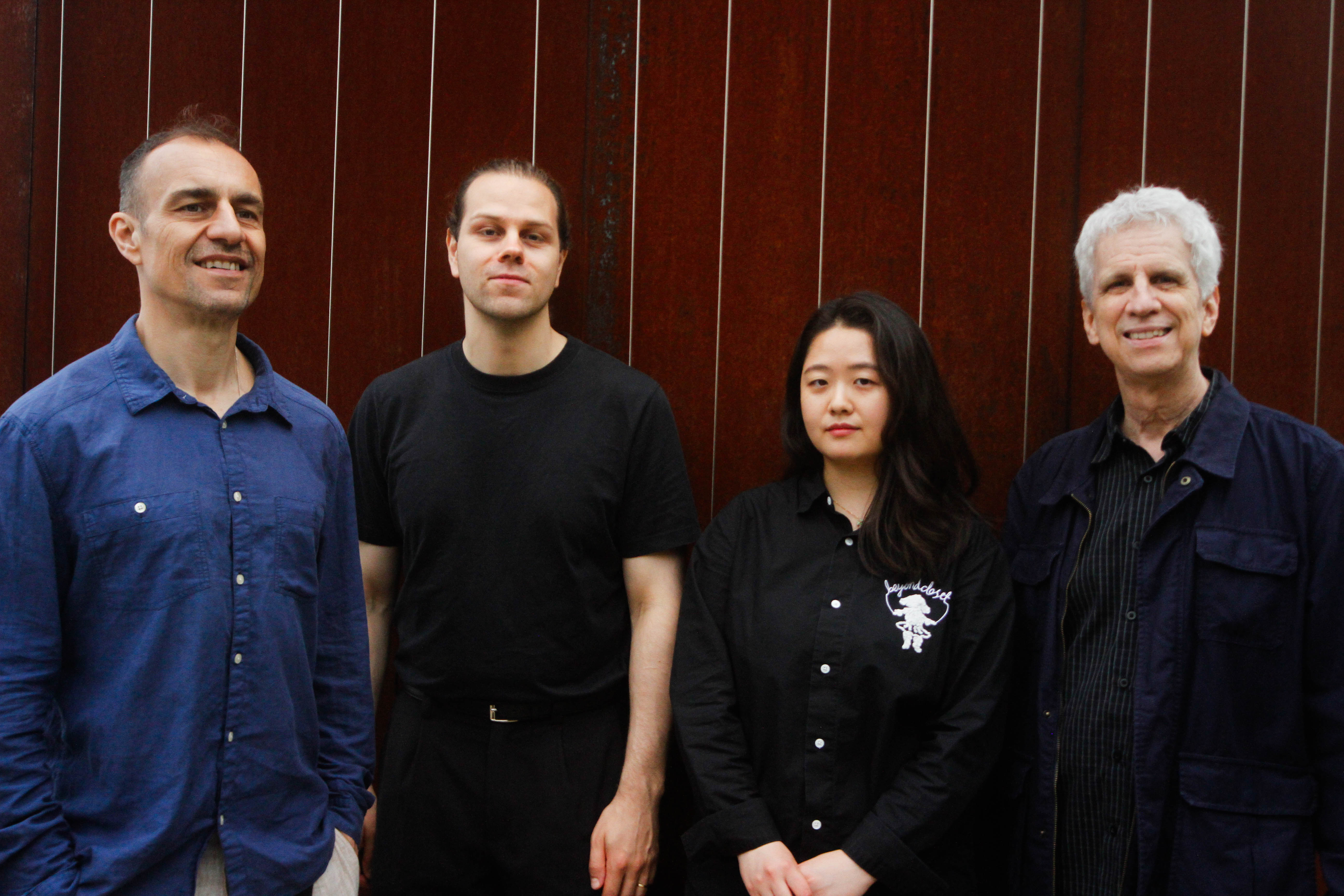

Jung Stratmann Quartet has released Confluence — an album featuring New York scene legends Steve Cardenas and Marco Djordjevic. Korean pianist Sujae Jung and German bassist Wolf Stratmann, in conversation with Indie Boulevard, explain how academic education coexists with spontaneity and why nature becomes a language for describing urban chaos.

Jazz education is always a game of balance: too much theory kills intuition, too little leaves a musician without tools for dialogue. Jung & Stratmann went through conservatories in The Hague and New York to ultimately create Confluence — an album where academic training and living energy don’t contradict each other but exist in a strange, almost symbiotic connection. The recording was done live before an audience, with no retakes allowed — a decision that says much about the quartet’s priorities. The studio brought together musicians from four countries with different pedagogical systems behind them. How do they find common ground? And what happens when a composition written for a duet suddenly grows to include guitar and drums — does it get diluted or, conversely, reveal what was always hidden?

In the conversation, we discuss how understanding of a partner’s music changes over years of working together, why trees and whales become metaphors for describing the expat experience in a metropolis, and how two musicians from Busan and Bielefeld attempt to compensate for the absence of nature in Manhattan’s concrete jungle. This is a conversation about the collision of worlds — academic and intuitive, urban and natural, student and professional — and about what emerges at the point of their intersection.

Hey guys, thanks for taking the time to chat with me. You and Sujae met at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague, then both continued your studies at The New School in New York. Over these years, you’ve evolved from a student duo to a quartet featuring legends like Steve Cardenas and Marko Djordjević. It’s interesting how many great jazz collaborations begin in academic settings but then get lost in the hustle of professional life. For you two, it’s the opposite—the partnership only deepens. Tell me, how has your musical understanding of each other changed since you first sat down to play together? What do you hear in each other now that you didn’t hear then?

Wolf: Hey, thank you! It is a pleasure for us, and we are grateful for being interviewed by you and the Indie Boulevard! Those are great questions to start with!

Sujae: Yes, they bring back some good old memories! Remember, Wolf, when you asked me to practise with you together for the first time after our first ensemble lesson back in fall 2019? Our teacher, Miro Herak, made us practice an F-Blues and mess around with rhythmical kicks, cross rhythms, and even shortening and lengthening the form. (Laughs) We couldn’t do any of it at first, but we kept on trying regardless until we managed that night in that room without a window in the old conservatory building. I was so tired afterwards, haha, but it was also so much fun!

Wolf: Ha, yes! As usual, you had it all down way before me and then helped me the rest of those hours patiently until I finally managed too! Haha

Sujae: I think that’s really a big one, after so much time of studying, practicing, playing, composing and working together, to know each other’s strengths and weaknesses so well. So we can really help each other out now, not only to make up for each other’s weaknesses but really make the other person shine and bring out the best in them.

Wolf: I agree. After all that, that is what this music is all about for us, the players, and who they truly are.

You recorded Confluence live in front of a select audience at Second Take Sound Studio. That’s a bold decision, considering the complexity of your material. What’s more important to you, technical perfection or that irreplicable energy that only emerges in the presence of people? And did you feel pressure knowing there wouldn’t be a second take?

Sujae: I would definitely go for the energy. Sure, you wish sometimes that you would like to have a second take on things, but then sometimes it gets too fuzzy anyway. Jazz for us has always been about community and connection in the first place. And in a concert, it’s almost like an exchange. You give something from yourself, you send it out while playing, and then you receive something back from the audience, of course. It’s much in a way like a shared process in which you might even learn something about the others and yourself.

Wolf: Totally! And even though we spend countless hours in the practice room, days and nights on end, in fact, honing our skills, all that matters is the very moment of the performance, it all comes down to. No matter how much you try to be perfect, the beauty of improvised music is that in the moment, it never goes as planned; everything is different from what you expected it to be. It’s just human, one day you feel like this, the next day like this. It doesn’t make sense to pretend that it’s different; otherwise, the conversation is not honest and might get very boring very quickly.

“Tree Huggers” exists in two versions—as a duo and as a quartet. You say you almost cried listening to the quartet version because each musician’s personality comes through so strongly and swirls together so gracefully. It makes you think about the nature of arrangement: sometimes adding instruments dilutes the original idea, and sometimes it reveals what was always hidden there. Sujae, when you wrote this piece, did you anticipate it would ever become a quartet piece? And what specifically changed in its emotional message when guitar and drums joined your dialogue?

Sujae: Most of the time when writing music, I try to have the players in mind that I want to play it with. Because all instruments sound so different depending on who plays them. With “Tree Huggers,” I was probably in one of those phases again, listening a lot to Keith Jarrett’s European Quartet Records with Jan Garbarek, Palle Danielson, and Jon Christensen. Wolf knows that music very well too, so with him, it’s easy going for that vibe. And then with Steve and Marko, it was so easy again because they totally understood where this piece was coming from. I think that’s why Wolf cried a little when listening back to our record, because he was so happy hearing that joy, liveliness, almost childlike bliss coming from the four of us playing together and letting it out.

You describe this album as an example of what “passing the torch” can look like in jazz. You’re playing with musicians who were your teachers at The New School— Satoshi Takeishi and Ned Rothenberg—but now you’re colleagues on stage, recording an album of your original compositions. Did something change in your relationship to them as musicians when the recording studio equalized you? And at what moment did you feel the transition from student to colleague was finally complete?

Wolf: To be very honest, I think this possibility of playing together happened initially because Steve and Marko never implied any hierarchy between us ever. I think it’s like one of our former teachers, Saxophonist David Glasser said once: “We are all on the same way, man. I’m just a little further down the road than you, standing there with a flashlight, lighting you the way.” Steve and Marko have shared the stage and life experiences with some of Sujae’s and my most favourite artists, some of which were undoubtedly integral to our artistic development. In the moment of performance, all these influences and experiences whirl together. It’s hard to put into words; it’s like something you can only really experience by playing or really deeply listening to one another. It’s like their influences shine through in their playing, and that influences and inspires us, their energy, their ideas, intentions, stories, and feelings.

Confluence described as nature-inspired—trees, whales, sunsets. But there’s something interesting happening here: you’re using the language of the natural world to describe deeply urban experiences of migration, displacement, and the pull of cities like New York. It feels like a kind of code-switching between the pastoral and the cosmopolitan. Is nature for you a way to process the chaos of being an expat musician in New York? Or is it something else entirely—maybe a way to stay connected to your roots while living this transatlantic jazz life?

Sujae: Yes, absolutely. We both come from cities where vast nature is really easily accessible. Busan in Korea, Bielefeld in Germany, and of course, where I met in The Hague, there is the North Sea just a short bike ride away from you, as well as that wonderful dune area, the nature reserve, Meijendel. New York is very intense in a way, everything here is artificial. A concrete jungle. You can not get anywhere without looking at commercials and ads. Nature here is optional to a large degree. Sure, you have Central Park or Prospect, but it takes an hour or even longer for us sometimes to get to those places, and then it’s never really quiet. To Upstate New York it takes even more than two hours sometimes. I feel like we have a kind a longing on one hand, which we try to compensate for with creating music that is inspired by nature, and on the other hand, we live and work in a metropolis that sustains our art. It’s this duality of our lives that sometimes cannot be merged, but then again, maybe they do live in symbiosis with one another.

You both received a Living Jazz “Jazz Camp West” scholarship in 2024, and you received the Dean’s Award at The New School for outstanding academic achievement. Academic recognition in jazz is a double-edged thing: on one hand, it’s validation; on the other, jazz has always been the music of outsiders, rebels, people who didn’t fit into institutional frameworks. Your education started with audio design and music production in Berlin, then jazz in The Hague, then New York. How do you merge the academic approach to composition with that raw, intuitive impulse without which jazz loses its soul? Does it ever seem to you that education can “over-teach” spontaneity?

Wolf: I might have had my moments where I have fought a bit internally with some academic systems that institutions have in place sometimes. But I would say in the end, I feel extremely grateful and privileged for the support I have received from the institutions where I was able to study. Although many of my past years were extremely challenging, these institutions really nurtured me to become the musician I am today. Studying music is also never just a plain study where you hang your head in the books and disappear into dry theory. It’s always like a dual degree kind of thing. You are working out stuff with people all the time, and then this takes you very quickly to opportunities outside of the Institution. It’s like music school is like a hub, a vast storage facility of invaluable quantities of information and resources, were you meet and make new friends, assemble tools, maybe get your butt kicked once or twice in a while gently by some of the professors, but then you got to take it all out to the gig, apply it and get on from there.

Confluence brings together musicians from Korea, Germany, the US, and Serbia—different generations and jazz traditions. But I’m curious about the practical reality of this internationalism. When you’re in a studio with musicians who were trained in different pedagogical systems, who listened to different records growing up, who have different cultural relationships to silence, space, dynamics—how do you find a common language? Is there a moment in rehearsal where you realize you’re not speaking the same musical dialect, and how do you bridge that?

Sujae: That is a great question, and I might be able to answer this with a metaphor, one of our former teachers, Saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom, once said so humorously: “It’s like as if we all stand around a chair in a circle. We all look at the chair from a different angle, and so each one of us talks about what we see from a different perspective. But in the end, we all talk about the same darn old thing. A chair.”

The album was mixed and mastered by Ken Rich at Grand Street Recording in Brooklyn. There’s been this ongoing tension in jazz between the “purity” of live, unprocessed sound and the possibilities of studio craft. Some purists say that too much mixing ruins the authenticity of jazz; others argue that’s a dated, fetishistic view. Where do you stand?

Wolf: We recorded all in one room, so naturally, there was quite some spill on all tracks. Jason Rostkowski did a great job in making the best out of the recording situation, but some of the bleeding is just unavoidable. Ken Rich then helped fantastically to clean up those tracks. For us, the mixing and mastering was about getting clarity to each instrument’s track, so that everyone’s ideas and playing can be heard and enjoyed well for the listener on any sound system they use. And that is really a must, in my opinion.

New York has changed dramatically in recent years. The jazz scene that drew you and Sujae there—the late-night sessions, the abundance of venues, the sense that you could stumble into genius on any given Tuesday—many say that’s fading or gone. Rents have pushed musicians out, venues have closed, the pandemic changed everything. Do you still feel that pull to New York as strongly as when you first arrived? Or are you and Sujae part of a generation that’s having to reimagine what a jazz career looks like when the traditional ecosystem is collapsing?

Wolf: That is a great question and a very timely one as well. In fact, we are leaving the States this December to first visit family in Korea and do a few months of study about Korean Traditional Music there, and then move to Germany for an indefinite time. Partially family reasons, but also political and economic ones, have brought us to this decision.

Sujae: Yes. We came to New York solely for the art scene, and I have to say we really found what we were looking for. For us, it still was an abundance of venues and a time filled with opportunity, so much that you sometimes had trouble keeping it all together.

Wolf: I get that point, that New York is changing drastically. But that is actually a large city’s constant: Change. The beauty is that people and cultures from all over the world stream in and out of the city for whatever reasons they may have for doing so. To be in that stream, that’s what it is about in the end. You might get swept away, but you’re certainly in for a ride! Haha

Sujae: In many ways, though, it is extremely tough as a foreign artist to sustain a living here. We have friends hustling multiple jobs and sacrificing their health to be part of it, just to have enough money to barely get by. In some cases, there is not much time left in a week to work on your own art. And that’s crucial, because you can twist and turn it however you want it, but in the end, as an artist, you need time to figure out what and how you want to create.

Wolf: Possibly, any generation has to reimagine a bit what the best way is now to have their music sustain them. But that is not necessarily tied to New York. It’s everywhere on our planet like that. In some places, however, the starting conditions might be a bit better than in others, and those impressions may vary from person to person as well, depending on their personal values.

Confluence out now. But jazz is ultimately about the live experience—the conversation between musicians and audience, the spontaneity that can’t be bottled. What are your plans for bringing this music to audiences in the flesh?

Wolf: Since we are leaving New York and we wanted to keep next year as open as possible for us to have enough room and time to decide where and how we want to start the next chapter in our lives, we have one concert this formation, scheduled. The album release concert.

Sujae: December 3rd, 7 pm at Ki Smith Gallery in Manhattan, New York!

New York, 170 Forsyth St, New York, NY 10002, USA

You can also find it here:https://www.kismithgallery.com/event-details/jung-stratmann-quartet-confluence-album-release-feat-steve-cardenas-marko-djordjevic

And in general, you can find out about all our other concert dates on our websites: https://www.sujaejungmusic.com, https://www.wolfrobertstratmann.com, and our Instagrams: @wolfrobertstratmann, @sujaejung_pi

*Promoted content. All information provided is prepared in accordance with editorial standards and is intended to offer useful insights for readers.